Myth-busting women in leadership and confidence issues

Having worked in women’s leadership development for two decades, there have been three key ideas that have provided much of the foundation around which women’s leadership development programs to date have been built.

They are:

- Women lack confidence.

- Women have imposter syndrome.

- Women don’t ask for what they want.

Personally, these narratives really grind my gears – not simply because I don’t like them, but more so because they lack accuracy, nuance and an understanding of how and why these ideas are so widely held.

Each of these ideas has gained a mythology that seems to provide a quick, simplistic answer to workplace gender equality issues including, the gender pay gap; less women than men holding senior roles; and workplace flexibility. Add to this trifecta discussions about biology and motherhood and you’ve got me rocking back and forth until I tap out!

Each of these three myths are inter-connected and reinforce a narrative that suggests that more feminised styles of leadership are problematic because they involve emotions (or emotional intelligence) and consider the needs of and impacts on others. They ignore the strength of the skills and abilities that it takes to really tap into and understand people and the tone of a situation. They come from an unconscious acceptance that leading and managing is about displaying over-confidence about our technical skills, intelligence and abilities; always working at speed; pushing for growth at all costs; and allowing or turning a blind eye to patterns of behaviour that are at best not well considered, and at worst, damaging for those around them.

The saddest part is that it is often women themselves buying into these narratives.

My coaching and workshop clients regularly say one or all of these three things about themselves. These are capable, senior professionals across the private and government sectors – senior lawyers (some partners), directors of departments, senior management in banks. They are highly competent, capable and accomplished. Often, they have more than one masters degree or even PhDs. Their credentials, technical skills and experience cannot be questioned.

When I ask them directly if they know the skills, capabilities and value they bring to their organisations, nine times out of ten, they most certainly do and can articulate them eloquently. They also have incredibly high levels of personal responsibility – they take their role as leading themselves and others very seriously and will look to themselves first if there is an issue or problem and ask “what can I do here to fix or improve this.”

However, they may still find themselves being promoted less quickly; not earning as much as their male colleagues (whether they know that or not); paying penalties (in salary, promotion or opportunities) for working flexibly; or simply not feeling their voices are fully heard at the decision-making table.

They may also be a recipient of some of the common generic and ambiguous feedback women seem to receive, like one client who recently told me that upon her promotion – to a role she had been acting in for some time prior – she was told: “We found that you have the technical competencies for the role. The outcomes you achieved and feedback from staff and stakeholders about you were outstanding. We do believe, however, that you may need to work on your confidence and presentation.” When she questioned what was meant by confidence and presentation she didn’t receive a very specific answer. To her credit, she took this feedback with grace, and summarised it back as, “I see, you think I have the substance but not yet the style!”

So let’s look a bit more deeply into myth number one – the confidence myth.

Myth 1: Women lack confidence.

Let’s start with a slight contradiction: a quick search of the internet and of some academic databases will indeed produce plenty of anecdotes and evidence that on self-report, women generally feel less confident than male participants do about their intelligence, skills and abilities. There have also been a significant number of books written on the subject, specifically for women, and some very compelling and offering practical tips.

However, the important question we need to be asking here is about what we are making this mean? How highly are we elevating the feeling of and display of confidence as a key indicator of good leadership? The answer to which is that we are often mistaking and conflating confidence for competence – and they are simply not the same thing and in fact, confidence is not even a great indicator of competence.

We are often mistaking and conflating confidence for competence

The Latin roots of the word are ‘con’ meaning together, with or all, and ‘fidere’ which means trust or reliance. If I say that I am lacking confidence, do I mean that I don’t trust my own skills, ability or competence?

If someone else suggests that I lack confidence, are they telling me that they don’t trust my skills, ability or competency? Or, are they suggesting that they think that I don’t trust myself? If the latter, is that correct or are they misreading something I’m doing or saying? For example, if I hesitate and take my time to respond to a question in a meeting, is that perceived as lacking confidence rather than thinking before I speak. Same if I ask to take a question on notice and check my data – is that perceived as lacking confidence when in fact I’m simply wanting to make sure we are getting this right.

Confidence is both an emotion and a display

Confidence is an emotion – which means that it is something fleeting. There is also a strong element of display to confidence: if I loudly, clearly and unwaveringly assert my viewpoint, it is more likely to be assumed that I am indeed competent. Research has shown that we often mistake displays of confidence for competency and often with disastrous results. Recently there has been much discussion of the Dunning Kruger Effect – a cognitive bias, (named after David Dunning and Justin Kruger), suggesting that people are prone to over-estimate their own skills and abilities (measured by asking them how they think they’ve gone in a task, versus how they actually objectively performed in a task). Interestingly, men are significantly more likely to over-estimate their intelligence, and women are more likely to under-estimate theirs. Studies find that men over-estimate their skills, abilities and intellect by around thirty percent – and that their over-confidence is not necessarily matched by their performance or outcomes.

In his books Think Again and Hidden Potential, Adam Grant discusses the important role that doubt and intellectual humility can play in creativity and decision making. There is no prize for guessing which gender is often better at displaying these two characteristics, yet we are not sending men on single gender leadership development programs to “fix” the “problem” of lacking intellectual humility. Consider, for example, the disproportionately high numbers of covid deaths that occurred in countries like Brazil, the United States and the United Kingdom when country leaders took “Let it rip!” approaches and were slow to walk them back, even in the face of strong and growing scientific evidence suggesting what was needed to be done. Unsurprisingly, countries with women leaders reported forty per cent fewer covid deaths between January and December 2020.

Countries with women leaders reported forty per cent fewer covid deaths across 2020.

This is not to suggest that there aren’t instances where women (and indeed others too) may benefit from displaying a bit more confidence, however, the point here is to have us think carefully about what we are judging and perceiving when we are making comments and assessments about confidence, and whether or not these are accurate ways of assessing a person’s leadership skills, abilities and competence.

We need to think carefully about what we are judging and assessing to be about confidence, and whether or not these are accurate ways of assessing leadership skills, abilities and competencies.

If the social norm for leadership largely looks, sounds and behaves in a particular way, whilst a small handful might question this, a vast majority will simply assume this as a given.

The way forward

So what can we do. If I had the proverbial ‘magic wand’ right about now I’d naturally want to ask for a whole of system over-haul, but failing that first preference, here are some starting thoughts:

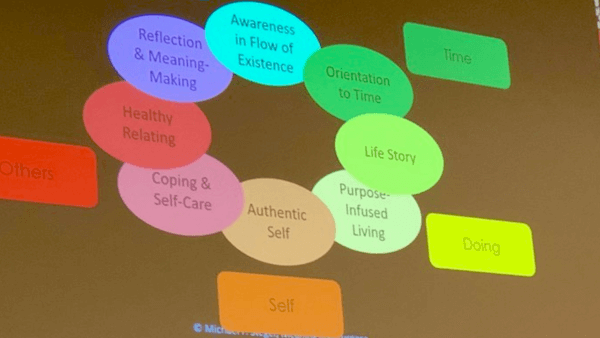

If you think you lack confidence at work

Firstly, if it is you thinking you lack confidence, curiously and kindly question what is meant by ‘confidence’ in your context? Get specific about what you need confidence in or about, or if you need to try on some different behaviour or thought patterns to move forward. Ask yourself: what is stopping me here? What would my idea of confidence be, feel and look like? Is it confidence, or it is something else?

If you get to the point where you are in your own head and ruminating for too long, sanity check your thinking with people whose advice you trust – and not simply those who will over-confidently tell you what to do! Also, consider your own strengths and style. The woman in my early substance vs style example was also paid an incredible compliment by one of the most senior figures in her profession who told her that he greatly valued and appreciated the calm and measured style and tone she had brought to a very tricky situation. She was really proud to be seen that way because she values calm and consideration and she wants to be that kind of leader for others.

Remember that questioning, reflecting, thinking, even doubting are positive, intellectual things to do.

It is when it flips into over-thinking, rumination on the same point over and over and ‘stuckness’ that we need the help of good sounding boards – friends, family, coaches, colleagues, trusted advisors and even sometimes counsellors and psychologists when our wellbeing is impacted.

Many of my clients are working through questions like: Do I really need that second masters degree or a PhD to be qualified enough for what I aspire to? Am I comfortable putting my name to the work we do – is this aligning with my values? Is the way we get work done in here a way that is productive, sustainable and healthy?

Rather than labelling these lines of questioning as a ‘confidence issue’ or ‘lack’ on your part, think about what you’re really wanting and go about asking for that:

- More information – what else do you need to know that will help you trust your decision-making and at what point are you prepared to not know?

- More time – does every decision need to be made “now” – if you are a brain surgeon in the operating theatre, ignore that question. If you are not, maybe reflect on this point a further.

- Maybe it is a skillset you don’t yet have – how can you get help with that for yourself or speak to someone who does have that skillset.

- A higher level of certainty - We would all love to be 100% certain before we make any decision and yet, that cannot always be so. What do you need to be certain enough to move forward in a direction in alignment with your values.

- Support – we often don’t ask for the support we need for fear of sounding needy. As a teacher at a university, one of the things I most love is helping my students learn and grow. Even though I’d love to think this is via my fabulous content, often it is really about hearing their questions and responding to them in a way that helps them to make sense of the content for themselves. Learning to really listen and hear as a leader and to use good, curious coaching questions to help them grow is an incredible confidence booster!

My team member lacks confidence

If you are a manager or leader describing your team member as lacking in confidence, check it with them first before permanently affixing the label. Read above to see some of things that they might be needing from you: often it is support and a good question to ask is: “how can I best support you?” and ask them to be specific with you. Also, we honest if there are things that you can not do to support them and help to clarify what your expectations of them are.

When I worked as a management consultant, one of the most helpful pieces of feedback I ever received went something like this:

Partner: When we go into our client meeting today, I really need you to be quite certain and definite in your words, language and facial expressions (yes, he did mention my face!), about the direction we’ve decided for the XX project.

Me: Sure – and help me understand: are there things I say or do that make me seem uncertain – and what do you mean by facial expressions.

Partner: One of the things I appreciate most about you is that you build great relationships with the clients and because of that, you have a strong influence over their levels of confidence in what we are doing. This is a tricky project, as you know, this client has changed their mind on multiple occasions, and we now have directives from above to cement this course of action. What you say, how you say it and how you react to their tendency to play devil’s advocate, could play a real difference here. I’ve noticed in recent meetings that you’ve supported the client in their questioning – and even added more questions, like in the <specific scenario given>. That has its place, but we have a strict time imperative and directive now to take action this way.

This feedback was helpful for me was because it was specific: I knew what was needed from me in that meeting and I knew why. I also felt valued because the partner had shown an understanding of what I was trying to do (maintain a strong client relationship and their trust).

What my Partner didn’t say – which he could have – is that I can be a bit verbose and love a brainstorm and ideas generation session, and so did my client. They and I could have happily used another meeting to do that, but the time for that was past. So there was no criticism or labelling of my style – just constructive feedback that told me what was needed for that meeting.

Is there something you are not trusting about their skills, abilities or leadership style?

As a coach I’m often ‘sent’ people to coach: “Please work with Janice as her confidence needs improving.” Depending on the relationship I have with the client, I will often say, “You used the word confidence which to me is about trust – what are you not trusting in Janice’s skills, abilities or leadership style?” Which is always followed by an insistence that “it’s not that I don’t trust her, BUT …” and the BUT can be any of the following (with many more thrown in):

- She doesn’t seem to trust herself (in other words, please fix her).

- She over-explains things.

- Women don’t ask for what they want.

- She doesn’t make a decision quickly enough.

- She just doesn’t have ‘Gravitas’ (this one is definitely code for: she doesn’t wear a suit; doesn’t exude over-confidence and either is softly spoken OR talks too much).

- She’s not proactive enough (proactive with what specifically?)

- She’s very nice BUT maybe too nice (so you want her to be ‘not nice’???)

I’ve had to cut the list above back as I could keep going but was starting to lose the will to go on…

Let’s draw upon our strengths of social intelligence, perspective, kindness, humility and even forgiveness and consider that there may be other ways of interpreting this than ‘lack of confidence’

You get the point: what the above resoundingly suggests is that she has some kind of problem that needs fixing. I’d like to instead suggest that we draw upon our strengths of social intelligence, perspective, kindness, humility and forgiveness (giving someone the benefit of the doubt), and consider that there may be other options for interpretation:

- Maybe we really haven't briefed or trained this person properly or been really clear on what our expectations are of them?

- Maybe we feel safer or more certain when a particular kind of voice, tone and style is used - and does that make this correct?

- Perhaps we find it too difficult to sit with doubt, discomfort and uncertainty – even though what our current world problems are demanding of us is better skills in this area (read up on adaptive leadership for more information on this).

- Maybe we don’t want to be shown to be wrong or look slow or incompetent in front of our clients or senior management – whereas maybe this is due diligence and careful consideration?

Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein said that “words create worlds” and I certainly have come to learn that the way we language, label and communicate impacts on our and other people’s thoughts, actions, behaviours and on our wellbeing – individually and collectively. Whilst we conflate confidence for competence, and whilst we privilege style over substance in our leaders, we enslave ourselves to leaders and leadership that are not up to the challenge of dealing with the complex issues of our workplaces and world today.

We can do better by starting with some curiosity, questions, and a desire to understand and appreciate styles that differ to those that have dominated the past.